- Home

- Maria Von Trapp

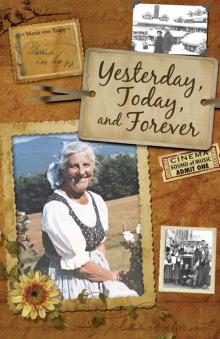

Yesterday, Today, and Forever

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Read online

Yesterday, Today, and Forever

MARIA VON TRAPP

Copyright Information

First printing: June 1975

Fifteenth printing: June 2009

1st printing in trade paperback

Copyright © 1975 by Maria von Trapp. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. For information write:

New Leaf Press, P.O. Box 726, Green Forest, AR 72638.

ISBN-13: 978-0-89221-696-3

ISBN-10: 089221-696-4

Library of Congress Number: 77153515

Portions of this book are from a book published in 1952 by J.B. Lippincott Company, Yesterday, Today, and Forever.

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture references are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

Printed in the United States of America

Please visit our website for other great titles:

www.nlpg.net

For information, please contact the

publicity department at (870) 438-5288

Contents

Preface — How It Happened

Part One — Yesterday

1. "In Those Days"

2. The Holy Land in Winter

3. Away in a Manger

4. Silent Night, Holy Night

5. Angels We Have Heard on High

6. Mary Pondered in Her Heart

7. The Purification and the Presentation

8. Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar

9. The Fugitive

10. "Unless You …Become Like Children"

11. "Did You Not Know …?"

12. The Carpenter

13. The Son of Man

A Word in Between

Part Two — Today

14. The Other Cheek

15. "I Have Called You Friends"

16. "He …Healed Them"5

17. "O Woman, Great Is Your Faith"

18. "The Woman"

19. "Christ …Lives in Me"

20. A Letter

Part Three — Forever

21. Blessed Are the Dead

22. The Judgment

23. "Begone, Satan!"

24. "No Eye Has Seen"

Endnotes

Preface

How It Happened

It was in Italian South Tyrol in a primitive little country inn on the edge of a lovely village in the mountains. The year was 1938, and this was the first station on our flight from Nazi-invaded Austria. We, that is Father Wasner, my husband, and I, and nine children with the tenth on the way, had just barely arrived at this peaceful little place when it happened. With a terrific wail, Lorli, aged six, discovered that we had forgotten her favorite toy, a worn-out, shapeless, hairless something, formerly a teddy bear.

The grief of a child is always terrible. It is bottomless, without hope. A child has no past and no future. It just lives in the present moment — wholeheartedly. If the present moment spells disaster, the child suffers it with his whole heart, his whole soul, his whole strength, and his whole little being. Because a child is so helpless in his grief, we should never take it lightly, but drop all we are doing at the moment and come to his aid.

I remember the situation so well, the glassed-in veranda in which we were standing, and me looking for a cookie or a candy, and there was none. Had I forgotten that we were refugees now, and luxuries like candies were things of the past? But even if the hands of a mother are empty, her mind and heart must never be. Taking the sobbing little girl on my lap, I said: "Come, Lorli, Mother is going to tell you a story."

That had always worked; but now it only brought forth new tears, and violently shaking her little head with its mop of dark curls, she shrieked, "I don't want to hear about Cinderella or Snow White — I want…."

"Oh no, Lorli," I said, "I'm not going to tell you one of those stories; but if you will listen to me, I will tell you the story of another child like you to whom the same thing happened — oh, a wonderful story!" And as I said this, I had no idea of what I was going to tell.

"Once upon a time," I began, "there was a mother, a father, and a little child."

"A girl?" Lorli managed to ask between sobs.

"No, a boy," I said.

At this very moment I saw them right before me, the holy family on their way to Egypt. For the first time, however, I didn't think of them the way the holy cards pictured them — Mary in blue, Joseph in brown, the little child in pink, each one with a golden hem on his garment — riding complacently on a neat donkey through a beautiful countryside full of date palms. For the first time it dawned on me that they were really refugees like millions of people nowadays; like ourselves, for instance.

"Flee," said the angel to Joseph, "flee into Egypt, for Herod will seek the child to destroy Him."

Wasn't the fright which must have chilled Joseph's blood at the moment the same fright which we had experienced so often when we heard the cruel stories of how the Gestapo was on somebody's heels, how they had dragged away fathers or brothers from families we knew? Wasn't it the same fright which had finally gotten us across the border? The angel had not announced to Joseph just exactly what Herod intended to do, but Joseph knew that Herod's Gestapo worked fast, and that his reputation for cruelty was unequaled. If the parents wanted to save the child, they had to hurry to get away from Herod. And while I told my little girl the story of the flight into Egypt, I listened to it myself. It was so new, so not at all holy-card-wise. It was so excitingly modern; the story of refugees, who, after having reached the goal, Egypt, became displaced persons — D.P.s. It was a story full of anxiety and homesickness, but also full of trust in the Heavenly Father, who in His own good time, provides a home for all refugees.

Lorli had long since stopped crying. In rapt attention she listened to my description of the dangers of the flight. I told about the wild animals and robbers, the terrific heat at noon and the cold at night on that dangerous passage through the desert, which even the Roman soldiers dreaded, and how the little boy did not make any fuss over a missing a toy, not once.

Then the angel of the Lord appeared again to Joseph, in my story, and bade him to return home.

"Will an angel tell our father, too, when we can go back to Salzburg?" asked Lorli eagerly.

"Yes," I said without the slightest hesitation, and a happy little girl glided down from my lap and ran off to Stefan, the innkeeper's little boy, to tell him this, her newest story.

Some of the older children had moved over from the other side of the veranda during the story. "Mother, that was really exciting," they said. I was completely taken with it myself. During the telling it had become clearer in my own mind: this story isn't over yet. All this is still going on.

"Children," I said, "I feel as though we are at the beginning of a great discovery. It seems as if Herod isn't really dead. He keeps living under different names, like Saul and Nero, or Hitler and Stalin. He still seeks the child to destroy Him." How close Our Lord and His family had become all of a sudden when we met them as fellow refugees!

That was a big discovery, and it came to us on the very threshold of a new life when we had joined the millions of refugees on the highways and byways of Europe in search of a new home. But I have told about all this in another book, The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, and I don't want to repeat any of it here. This is to be simply the story of how "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever" (Heb. 13:8) — and how He finally became a member of our family.

In that summer of our flight through Europe we had another startling experience. It was a few weeks after the incident on t

he glassed-in veranda. One of our sons was engaged to be married, and his bride-to-be spent several weeks with us in Holland. One day she came to me and said, "Mother, can you tell me what he was like when he was a baby? He has told me everything about his life as far as he can remember, but — I want to know all."

That hit me right between the eyes. Reading the Gospels together and searching in them for more modern stories like the one of the flight into Egypt had become a family hobby by then. Merely by doing it we had found out how little we knew about our Lord and His family, His country, and His times. Aside from stating the fact, we hadn't done anything about it. Then came this girl who went out of her way to find out every detail about the one whom she loved because — "she had to know all." This did something to us.

"How can we pretend to love our Lord," we said to ourselves, "if we don't want to know all about Him as well?"

On that same evening during night prayer it occurred to me that Mary, the mother of Christ, was a mother like me. Perhaps she would be just as pleased about the questioning as I had been, so I turned to God and said, "Father, there is so little written in the Gospels about your Son when He was a Child and while He was growing up. How was it in Nazareth, in Bethlehem, in Egypt? Was He lively or was He rather quiet? What did He eat, what did He wear? What did He do all day long, and what about Joseph?

I don't believe in chances and coincidences. It must have been she who gave two friends of ours, independently of each other, the idea to present us with books: The life of Our Lord Jesus Christ by the German Jesuit Maurice Meschler, and Life of Jesus by Francois Mauriac.1 There could hardly be found a greater contrast than between those two works on the same subject. That was the beginning of a very helpful little library of our own. After we had finished these two books, we wanted to know more. And more. And more. God has never stopped answering our questions. Besides helping us find the right books, He also helped us remember what we had once learned in history, geography, archaeology, and religion. He drew our attention to the fact that besides the four canonical Gospels there is something else which we can almost regard as a "fifth Gospel," so much a source of information it is: the Holy Land itself. Very much of it is still exactly the same as it was in His time. There we started getting interested in maps of the modern and ancient Holy Land.

Many years have passed since. After we had shared with Him the anxiety of the flight, we lived through years of the "hidden life," and then through the excitement of the "public life." Many notebooks have been filled with information which we drew out of different books, which seem to complement each other. Pictures of the Holy Land have been cut out of magazines throughout the years, and postcards sent to us from there by friends have been collected. Putting all these different pieces together is like assembling a crèche.

Every time we say the Creed, we say toward the end that we believe in the communion of saints.

Of the Early Church it is said, "The multitude of those who believed were of one heart and one soul: neither did anyone say that any of the things he possessed was his own, but they had all things common" (Acts 4:32; NKJV). That did not refer only to money and the things money can buy, but also and foremost to spiritual goods. We know from the Acts and Epistles of the Apostles and the writings of the early fathers that this was true. Haven't we moved far away from those times? While we still might share our earthly possessions and contribute to collections, we certainly are not in the habit of sharing our spiritual goods any more. This is our innermost private life, and what I learned this morning in meditation or what occurred to me during reading is nobody's business. This is the spirit of "I-me-myself," whereas the right spirit is always "we-our," as we find in the liturgy, in the prayers of the Church. This would make the difference between a family and a group of people living together under one roof.

It is in this spirit that we want to share with you our great discovery — the bringing of the Holy Scriptures to life for us, and, by watching Him, learning to imitate Him, learning how to live, how to love, how to die. In the world situation of today it may look like five minutes to twelve, but if we Christians would wake up to the meaning of our name and become "other Christs," we might bring about what was promised only to men of good will: peace on earth.

Part One

Yesterday

Chapter 1

“In Those Days”

Whenever we read the life story of one of the great ones, be it Washington, Lincoln, Napoleon, or Julius Caesar, we always find that the biographer takes pains to picture for us the time in which his hero lived, thus helping us to understand certain features of his character and certain happenings of his age. So Luke, the biographer of Christ’s childhood, does the same. “In those days,” he says, “a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be enrolled” (Luke 2:1).

“In those days.” That means the time when in Rome the nephew of the great Julius Caesar had become emperor. His real name had been Octavius, but his soldiers hailed him as “Augustus.” In those days the Roman troops had been victorious almost to the ends of the then-known world. They had invaded country after country in many bloody wars, but now the whole empire was at peace. Before Augustus came into power, terrible civil wars had raged. These and all the invasions had exhausted the finances of the empire, and so Caesar Augustus used this new peace to think of new means to fill the coffers of the state. His new idea was to get every single one of his subjects, without exception to make a contribution. To help the publicans, or tax collectors, in their business, he ordered now, like the owner of a big department store, an inventory to be made.

“In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be enrolled” (Luke 2:1).

“All the world” — what a proud phrase! But these were almost the facts. Almost all of what was then known of the world was ruled by Roman governors according to Roman law, and the Roman legions watched on the borders.

In those days one of the most important provinces was Syria, and the official in charge of the census in this province was Quirinius. Tucked away in one corner of his province was a tiny little kingdom of Judea, with Herod as its king.

When Caesar Augustus decided on the census, messengers on horseback galloped along the famous Roman highways carrying the new law north and south. At the same time, fast galleys left the Roman ports to take the message across the seas. One of them would arrive in Syria, and Quirinius would sub-delegate King Herod to carry out the census in his land. Herod, who owed his kingship to the Romans, would be only too eager to oblige.

These enrollments were usually made in the places where the people lived. But the Jews had a different custom, and it had always been the policy of the Romans to respect the local habits and customs of conquered nations. Since ancient times the Jews had been divided into tribes. To each tribe belonged a certain county of Judea/Samaria with a family headquarters.

Joseph belonged to the tribe of Judah and to the house and family of David. The place where David the king had been born and raised was Bethlehem, which later became the headquarters of the House of David. When, therefore, on a certain winter day a messenger came to Nazareth, the little town of Galilee, reading aloud to all the men the imperial decree, “all went to be enrolled, each to his own city. And Joseph also went up from Galilee, from the city of Nazareth, to Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and lineage of David, to be enrolled with Mary, his betrothed, who was with child” (Luke 2:3–5).

Chapter 2

The Holy Land in Winter

When my husband was still in the navy, he once spent some time in the Holy Land. It proved to be wonderful for us later. When, for instance, we wanted to find out about that winter journey of Mary and Joseph from Nazareth to Bethlehem, we simply said, “Tell us, what is the Holy Land like in winter?”

“Oh, well,” he used to say, “that depends upon where you are. Small as it is, the country has three distinct zones. There is that de

ep gully, the Jordan Valley, below the level of the Mediterranean. There it is always covered with snow. The weather there I found very much like the Alps. At the same time, there is the rather mild climate in the hill country, Galilee, Samaria, and Judea. But why do I say ‘mild’?” he corrected himself. “In the winter, that means in the rainy season, it can be simply awful. The rains start in October and last until March. ‘It never rains but it pours,’ one can really say of those tropical showers. The winds blowing down from the mountains are ice-cold.”

“It was about 30 years ago,” said my husband meditatively, “when our ship anchored in the Bay of Haifa, and all the officers were invited by some Arab sheik to make a trip on horseback throughout the country. That was before the times of modernization. No bulldozers had yet reached the Holy Land and we were assured time and again that what we saw was pretty much as it had been since time immemorial.

“We were there around Christmastime. The rainy season had been going on for almost three months, and the moment one left the highway, the horse sank in the deep mud. We were astonished to find everywhere the peasants in their fields plowing and sowing, and we asked why they didn’t wait for the dry season. But we were told that the sun bakes the earth so terribly that the primitive plows couldn’t break the hard soil. I remember we usually saw groups of plowmen working together with their tiny oxen and little plows, merely scratching furrows. We used to stop our horses and watch them for a little while. Often they were shivering in the cold. One old man I remember was holding a basket of seeds, and with tears in his eyes, complained to our interpreter about the weather. When I think of him now in his brown woolen tunic, soaked through and heavy with rain, I can imagine what Joseph must have looked like.”

From there we went on to figure it all out for ourselves: Mary and Joseph locking up their little house in Nazareth and setting out in the rain on their 80-mile trip. Mary was in no condition to travel. She expected her child any day now, but obviously the census was meant for men and women alike, and Mary, knowing that the Messiah had to be born in Bethlehem, knew she had to go. They were not rich enough to afford camels, the only convenient way of travel in those days, but they took a donkey. No saddles or stirrups were used at that time. Mary had to sit on a folded blanket laid across the sharp-pointed back of the little animal. How long would it have taken them to reach Bethlehem? From the writings of Julius Caesar, we know that the Roman soldiers were supposed to make 20 miles daily when they were not armed, and 12 miles a day under arms. But those were sturdy, strong young men, and here was a young mother expecting her first child within a few days. She surely couldn’t make more than 12 miles a day.

Yesterday, Today, and Forever

Yesterday, Today, and Forever